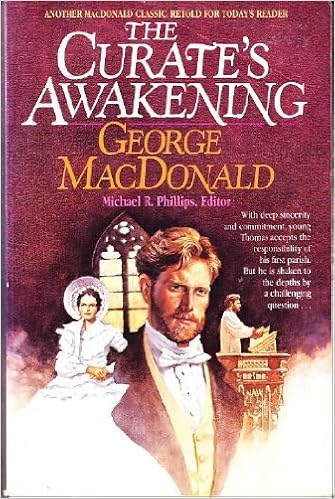

I am currently reading an anthology of George MacDonald entitled Discovering the Character of God. For those who are unfamiliar with MacDonald, CS Lewis counted him among his greatest influences. I read this page this morning, a passage from his fictional The Curate's Awakening, and I was deeply struck.

I am currently reading an anthology of George MacDonald entitled Discovering the Character of God. For those who are unfamiliar with MacDonald, CS Lewis counted him among his greatest influences. I read this page this morning, a passage from his fictional The Curate's Awakening, and I was deeply struck.The morning which had given birth to the stormy afternoon had been a fine one, and the curate had gone out for a long walk. Not that he was a great walker, his strolls were leisurely and comprised of many stops. He was not in bad health and was not lazy. Yet he had little impulse for much activity of any sort. The springs in his well of life did not seem to flow quite fast enough.

He sauntered through Osterfield Park and down the descent to the river. There he seated himself upon a large stone on the bank. He knew that he was there and that he answered to "Thomas Wingfold;" but why he was there, and why he was not called to something else, he did not know. On each side of the stream rose a steeply sloping bank. on which grew many fern brushes, now half-withered. The sunlight upon them this November morning seemed as cold as the wind that blew about their golden and green fronds.

Thomas felt rather cold, but the cold was the sort that comes from the look rather than the feel of things. With his stick he kept knocking pebbles into the water and listlessly watching them splash. The wind blew, the sun shone, the water ran, the ferns waved, the clouds went drifting over his head--but he never looked up or took any notice of the doings of Mother Nature busy with her housework.

His life had not been particularly interesting. He had known from the first that he was intended for the church, and had not objected but accepted it as his destiny. Yet he had taken no great interest in the matter.

The church was to him an ancient institution of approved respectability. He had entered her service, and in return for the narrow shelter, humble fare, and not quite shabby garments she allotted him, he would perform her observances.

Thomas did not philosophize much about life, nor his position in it. Instead, he took everything with an unemotional kind of acceptance and laid no claim to courage or devotion. He had a certain dull prejudice in favor of not telling a lie, and yet was completely uninstructed in the things that constitute practical honesty. He liked reading the prayers in church, for he had a somewhat musical voice. He visited the sick--with some repugnance, it is true, but without delay--and spoke to them such religious commonplaces as occurred to him.

He did not read much, browsing over his newspaper at breakfast with polite curiosity sufficient to season the loneliness of his slice of fried bacon, taking more interest in some of the naval intelligence than in anything else. Indeed, it would have been difficult to say in what he did take much interest.

Could he in all honesty have said he believed there was a God? Or was this not all he really knew--that there was a Church of England which paid him for reading public prayers to a God in whom the congregation was assumed to believe?

It was not a question Wingfold had yet considered.

No comments:

Post a Comment